A story of strength, perseverance and Stringer

By Mechelle Voepel

Special to ESPN.com

No matter how many times you read or write C. Vivian Stringer's story, you still can't quite believe it. It gets more amazing, more touching, more heartbreaking, more inspiring.

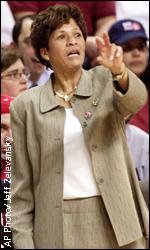

|  | | Coach C. Vivian Stringer has won 621 games. |

It's not as if you can imagine actually going through it, let alone achieving what she has through it. But Stringer isn't going to claim she's anything particularly special. You get by, you survive because ... what else are you going to do?

Each morning keeps arriving, each obligation remains. You either accept it or you don't. And if you don't, you stop surviving. It's that's simple, and that difficult.

So when Stringer's Rutgers team meets Tennessee tonight in the national semifinals, in Philadelphia of all places, you should think about fate and how it brought Stringer back here.

What's that they say about God never shutting a door without opening a window? How come Stringer's windows have always been tiny, high at the top of the building, hard to reach?

But more than that, how has she always managed to get through them?

"I don't really know what it's like to be at a Final Four," Stringer said, "and to be free in terms of being able to focus on the work at hand and not have a lot of personal hurt that I'm dealing with."

Again, if you're a women's basketball follower, Stringer's story is probably familiar to you. Yet to hear it again makes you realize all over what real courage and determination are about.

Go ahead, put yourself in her shoes.

You have a little daughter in the hospital while you are trying to coach your team in the very first NCAA Final Four in 1982. You're going between Philadelphia, where your daughter is, and Virginia, where your team is.

They tell you this little girl is going to be disabled for the rest of her life, that she will need constant care, that she will be robbed of things all of us who are healthy take for granted. You are someone who devotes her life to other people's daughters, and now you find your own daughter will have none of the opportunities that they have.

The hopes you might have had for her? They all change. Now, your only hope is she might live, and you might make her life as good as it possibly can be.

How do you fight that rage, that sadness, that guilt that somehow you weren't supposed to let this happen, that somehow you could have prevented the unpreventable, that agony of thinking if only it could have happened to you instead, not your baby.

How do you fight that? You work. You lean on those who love you. You ask God to help.

Stringer did all those things, and then she left Cheyney State for Iowa. A new start at a program that needed her, a place where she also took a team to the Final Four.

But then again, put yourself in Stringer's home, Thanksgiving Day, 1992. You call out to your husband, the person who has always there when you're tired, who's always there for your daughter, who seems as strong as a human being can be. He doesn't answer. His heart has stopped.

The terror, the disbelief, the fury, the grief. How do you get through that?

You repeat the process of before, except maybe this time you have to ask for just a little more help.

Then, another window. Rutgers offers you a job, a chance to go back closer to your roots and away from a place that holds too much pain. You go, but the expectations are high. Why? Because you made them high. You promised, and your first two years you're just trying to move the pieces into place. You know there are doubts, but you don't care.

Anyone who doubts you has probably never heard your story.

Then the year the Final Four is in Philadelphia, the town where much of this story started for you, your team comes together at the right time. They are young women who see you as nothing but strength, who hang on to pretty much your every word. They've come through for you, and you for them.

As teams took the court Thursday to prepare for today's national semifinals, Stringer was asked about her three Final Four trips, to talk about how that journey and those teams paralleled the development of women's college basketball itself.

Stringer speaks in almost a stream-of-consciousness style. You do not ask her a question unless you are ready to listen, to follow along where her mind goes when she takes journeys into the past.

She remembers that first Final Four ... it wasn't so much about the event as just more games to be played. You win, you keep playing. That's what Stringer wanted to do: Keep playing. She didn't even want to stop if Cheyney had won the championship. Couldn't they just keep playing?

She remembers leaving Children's Hospital in Philadelphia to go to practice. Having to leave her girl for her other girls. Both needed her. And she was there for both.

She remembers Iowa, how things were good and then, suddenly, they weren't. And finally, she remembers the players. Like those from Cheyney State that first Final Four year, women who are now approaching their 40s. Women who always will be kids in Stringer's mind, the way they were then.

"My enthusiasm is exactly the same, but I think that when I look at this press room and all the people that are here, this was nowhere near the kind of size that was there in '82 at Old Dominion," Stringer said. "There has been a tremendous revolution that has taken place."

One of the fighters in that revolution? A woman who has taken every cruel, inexplicable blow life can offer and still fights. Still shows others how to persevere.

People talk a lot at the Final Four about dreams. They're usually about winning national championships. You know that Stringer might win one, if not this year, some year. And you know it will be a sweet moment.

But you also know she has other dreams, about a husband, a daughter, a family that someday, somewhere, somehow might be. Those dreams won't be realized on a basketball court, won't be symbolized by a trophy, won't happen on this earth.

But here's hoping all of Stringer's dreams come true.

Mechelle Voepel of the Kansas City Star is a regular contributor to ESPN.com. She can be reached via e-mail at mvoepel@kcstar.com. |