|

|

|

|

|

| ||

|

Scores Schedules Standings Statistics Transactions Injuries: AL | NL Players Weekly Lineup Message Board Minor Leagues MLB Stat Search Clubhouses | ||

| Sport Sections | ||

|

| ||

| TODAY: Monday, May 15 | ||||||||||

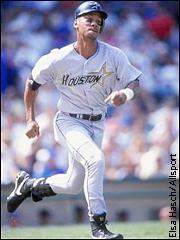

| Houston Astros Special to ESPN.com | ||||||||||

Record: 97-65, tied for 4th overall Payroll: $56.4 million, 10th overall Runs scored: 823, 8th in NL Runs allowed: 675, 2nd in NL What went right? Jeff Bagwell played in every game, hit .304 with 42 homers, stole 30 bases, and led the majors with 149 walks and 143 runs scored, losing the MVP award only because Chipper Jones was unstoppable in September. Mike Hampton went 22-4 with a 2.90 ERA, and finished second to Randy Johnson for the Cy Young Award. Jose Lima guaranteed he'd win 20 games and then won 21, and Billy Wagner had a 1.57 ERA, blew only three saves all year, and set all-time records with 14.95 K's per nine innings and 3.54 strikeouts for every hit allowed. Young Scott Elarton provided a glimpse of the future, going 9-5, 3.48 as a swingman. Carl Everett had a breakout season, hitting .325 with 25 homers and 108 RBI in just 123 games. Craig Biggio, even having an offseason by his standards, hit 56 doubles; no one has hit more since Joe Medwick had 64 in 1936. What went wrong? Bagwell and Biggio once again didn't hit at all during the playoffs, and in the pivotal Game 3 of the Division Series, the Astros loaded the bases with nobody out in the bottom of the 10th inning against the Braves, but failed to score the winning run. They lost in the 12th inning and were eliminated the next day. Moises Alou tore his ACL before spring training and missed the entire year. Highly-touted rookie catcher Mitch Meluskey played only 10 games before having shoulder surgery that ended his season. Derek Bell was a joke, hitting just .236 with 12 homers. Chris Holt returned after missing all of 1998 from arm surgery, but lost his first six decisions and finished 5-13. Ken Caminiti and Ricky Gutierrez both missed half of the season with injuries. Elarton was found to have a partial tear of his rotator cuff after the season ended, and required surgery. And financial considerations led to the trade of Carl Everett to the Red Sox (for shortstop prospect Adam Everett) and Hampton and Bell to the Mets (for Octavio Dotel and Roger Cedeno). In retrospect, the critical decisions were: 1. Bowing out of the Randy Johnson sweepstakes. It's understandable that the Astros felt they couldn't top the Diamondbacks' offer of $13 million a year for four years, but Johnson now looks like a bargain after his Cy Young season. Given how good a pitcher's park the Astrodome is and how well Johnson pitched for the Astros in 1998, you have to wonder just how incredible his season would have been had he stayed in Houston. 2. Trading Brad Ausmus and C.J. Nitkowski to Detroit. It looked like the right move at the time, giving a fair shot to Meluskey. But while Ausmus and Nitkowski both had good seasons, Meluskey hurt his shoulder, leaving the Astros to limp through the season with Tony Eusebio and Paul Bako as their catchers. None of the players acquired from Detroit amounted to anything, and the Astros didn't clinch the division until the last day of the season. 3. Trading Carl Everett and Mike Hampton away before they reached free agency. Astros fans are understandably upset their team would trade away two of their best players to save money just as they're entering a new ballpark. But by moving Everett and Hampton (and malcontent Derek Bell), the Astros aren't just saving nearly $15 million in salary; they've also picked up a premier leadoff hitter (Roger Cedeno), a starting pitcher who held opposing hitters to a .226 average as a rookie (Octavio Dotel), and a potential shortstop of the future in Adam Everett. While these trades could cost the Astros a few games this upcoming season, they go a long way towards keeping the team competitive for another five or six years. Looking ahead to 2000 Three key questions 1. Can they defend their NL Central title while reloading? With the trade of Hampton, their best starting pitcher, and Carl Everett, their best outfielder, the Astros need their replacements -- Dotel and Cedeno -- to play at least as well as they did for the Mets last year, and they need other players to step up their performances to pick up the slack. 2. Will the second time be the charm for Mitch Meluskey? After hitting .353 with a .465 OBP and a .584 slugging average in Triple-A in 1998, Meluskey was thought to be a Rookie of the Year contender last year, but required surgery on a chronically dislocating shoulder. He returned to play in the Arizona Fall League, and the Astros are hoping a healthy Meluskey will help an offense that dropped from first to eighth in the NL in runs scored last year. 3. Can they turn things around in the playoffs? Assuming the Astros make the postseason again, they have to find a way to improve on a 2-9 record in their last three trips. Bagwell and Biggio have a combined .123 average in the postseason, with one extra-base hit in 81 at-bats. That has to improve. Can expect to play better Richard Hidalgo. After hitting .303 as a rookie in 1998, Hidalgo hit just .227 last year -- but was hitting .261 in mid-June before his season was ruined by a pair of knee injuries. He also hit 15 homers and drew 56 walks in just 108 games. Just 24 years old, Hidalgo could be this year's Roger Cedeno if he can stay healthy. Can expect to play worse The pitchers, in general, since Enron Field is unlikely to be as tough on hitters as the Astrodome was. Jose Lima's a good pitcher, but when you win 21 games despite a 3.58 ERA, you're not just good -- you're also lucky. Projected lineup CF Roger Cedeno 2B Craig Biggio 1B Jeff Bagwell LF Moises Alou/Daryle Ward 3B Ken Caminiti RF Richard Hidalgo C Mitch Meluskey/Tony Eusebio SS Tim Bogar/Adam Everett Rotation/Closer Jose Lima Shane Reynolds Octavio Dotel Scott Elarton Chris Holt/Wade Miller Billy Wagner A closer look As the Astros prepare to do battle for their fourth straight division title, more than the usual set of questions remain. Not only do they have to fend off a charge from the Cardinals, who have finally figured out that they might be a better team if they had some pitching to go along with Mark McGwire, but they also have to hope the gamble to trade Mike Hampton and Carl Everett -- before they walked away of their own volition -- doesn't blow up in their face.

But there's a new and mostly unrelated question that adds a quirky twist to the Astros' season: how will their new ballpark affect the team? The question isn't so compelling because of what Enron Field is, but rather, what it isn't. It isn't the Astrodome, known the world over for the space-age design that ushered in a new era in stadium architecture, but better known in baseball for its offense-sucking powers that has frustrated hitters and delighted pitchers for over 30 years. Last year, for example, the Astros and their opponents combined to hit 157 homers in 71 road games (ignoring interleague contests). In 76 NL-only games at the Astrodome, only 110 homers were hit -- meaning the Astrodome reduced homers per game by 33 percent. That figure is hardly unusual. In 1991, the Astrodome cut homers by 48 percent, and in 1983 and 1984, the reduction was an amazing 62 percent. At the same time, the tough hitting background has increased strikeouts by an average of 12 to 15 percent. As a result, the Astros have typically had success with power pitchers (remember Mike Scott?), while power hitters have been rendered nearly impotent. All of which makes the success of Jeff Bagwell all the more amazing. There's a popular sentiment that a "true" power hitter can hit homers in any park, as if "true" power hitters only hit 500-foot homers and never hit flyballs that just clear the fence. How silly. When the Texas Rangers moved into their new ballpark in 1994, they felt that the deep dimensions in left field wouldn't affect Juan Gonzalez. Wrong. In his first year at The Ballpark in Arlington, Gonzalez's homers dropped from 46 to 19. While his power did recover, Gonzalez has hit just 97 of his 219 homers (44 percent) at home since moving into the new ballpark. The hitter who lost the most homers to his ballpark in the history of baseball? Joe DiMaggio. The same goes for Bagwell, who has hit just 126 of his 263 career homers (48 percent) at home. Last year, he hit thirty homers on the road, but just 12 in the Astrodome. Compare his homer totals to two far-more-publicized sluggers: Name Home Road Total Bagwell 12 30 42 McGwire 37 28 65 Sosa 33 30 63Bagwell hit more homers on the road than McGwire, and as many as Sosa, yet didn't come within 20 homers of their overall totals. His partner in crime, Craig Biggio, has been similarly stifled by the Astrodome: only 64 of his 152 career homers (42 percent) have come at home. Let's take a look at his numbers over the last five years both home and away, scaled down to 650 plate-appearances to make the comparison easier: AB H D T HR AVG OBP Home 578 170 37 3 15 .294 .395 Away 575 180 37 3 20 .313 .403It's safe to say that the Astrodome has cost Biggio 20 points of batting average and 3-4 homers a year, making his performance all the more remarkable. The flip side to this is that the Astros' pitchers have garnered a significant advantage from pitching inside the Eighth Wonder of the World. And none more so than Jose Lima, a pronounced flyball pitcher who has taken more than the usual advantage from his home dwellings. Since joining the Astros in 1997, here are Lima's home-and-away splits, pared down to 220 innings apiece: IP H ER W K HR ERA Home 220.0 200 71 37 183 20 2.90 Away 220.0 247 117 36 150 37 4.79On the road, Lima is not even a league-average pitcher, giving up a home run every six innings. But when he's throwing in the Astrodome, his home runs are shaved nearly in half and his ERA drops by nearly two runs. Can we expect Enron Field to be more hitter-friendly than the Astrodome was? Let's take a look at the dimensions for each park: Park LF LCF CF RCF RF Astrodome 325 375 400 375 325 Enron Field 315 362 435 373 326From center field to the right-field pole, Enron Field doesn't appear to be any more home-run friendly than the Astrodome was. But in left field ... 13 feet might not sound like much, but it is. The distance to the power alleys has the greatest impact on hitting home runs, and 13 feet is greater than the difference between Comiskey Park (375 feet) and Tiger Stadium (365 feet). Even with a 21-foot-high fence in left field, it's safe to say that more balls are going to clear that fence in the new ballpark. The distance to the outfield fences doesn't give you the whole picture. Other factors are: 1. Foul area. The distance from home plate to the first row of the seats in the Astrodome was 52 feet. At Enron Field, it will be 49 feet. Overall, there should be slightly less room for fielders to snare foul pop-ups. 2. Climate. Whereas the Astrodome was climate-controlled, Enron Field will have a retractable dome that can let the elements in. Houston in the summer is notoriously hot and muggy. According to Robert K. Adair's book, "The Physics of Baseball", both high temperatures and high humidity will increase the distance of a batted ball -- making Enron Field potentially even more of a hitter's park. (Then again, on a really hot and muggy day, the dome will probably be closed.) 3. Surface. The Astrodome, of course, had Astroturf. Enron Field, of course, is a field -- a grass field. Turf fields, on the average, tend to increase doubles and triples as balls skip past outfielders into the gaps more quickly. The Astrodome has increased doubles by 11 percent and triples by 31 percent over the last three years; Enron Field is likely to be much less friendly in that regard. Add it all up, and Enron Field figures to be about a league-average park for offense -- in other words, it's going to be a much better place to hit than the Astrodome was. It might even be a slightly above-average home-run park for right-handed hitters. Meaning that while it might be "Lima Time" a lot less often in south Texas this year, if Bagwell makes a run at 60 homers, the Astros won't mind at all. Rany Jazayerli, MD, is co-author of the annual Baseball Prospectus, a hard-hitting, irreverent, no-holds-barred look at our national pastime. Look for the 2000 edition in bookstores Feb. 1. He can be reached by email at ranyj@umich.edu. | ALSO SEE Astros minor-league report ESPN.com's Hot Stove Heaters  | |||||||||