| | This is Alonzo Mourning's year, his time, and it just seems the strangest

moment for this grim chapter in his life to be unfolding. As he waits to tell

the public the details of his apparent kidney disorder, there has to be a

part of Mourning wondering not just, "Why me?" but "Why now?"

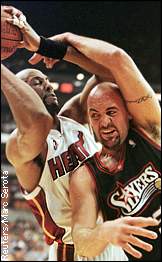

|  | | Mourning now isn't fighting opposing centers, but a different opponent. |

There are no proper candidates for this crises to come calling on, no

right moments, but Mourning was dancing on stars until these troubles hurled

his life into an uncertain dark abyss. He had an Olympic gold medal, the

birth of his baby girl and a season, a team, waiting to take him to the NBA

Finals.

Most of all, Mourning had peace of mind. For so long, he was desperate

for the world to see the good man beyond the scowling face, to see the

gentle, generous giant trapped too long within the walls of the bravado. He

had to break free of the Georgetown mold, the Hoya paranoia and over time

Mourning did it. Off the court, Mourning finally understood he didn't have to

play the part.

Long before the Heat's center had come home from the Olympics, had a blood

test and started down this frightening road, he had come to a most

important crossroads in his life. Finally, he let go. He stopped the sulking,

the brooding and offered a different face. He let people see him laugh,

listen to his thoughtful way and Mourning worked relentlessly to shed the

image that chased him to the Heat five years ago.

It was a long, hard journey to peace of mind for Mourning. Just now,

Mourning had started to reap the rewards. Even his most embittered rivals,

the New York Knicks, had come to understand they had misjudged him. At the

2000 All-Star Game in Oakland, Jeff Van Gundy approached Mourning to tell him

he was sorry for the wild melee two years ago in the playoffs, when the

coach clung to Mourning's ankle in Madison Square Garden.

"Forget it," Mourning said, and the two of them proceeded to laugh long

and hard.

Just this summer, Allan Houston was a member of the Dream Team at the

Sydney Games. When it was over, Houston was asked: Which USA teammate

surprised him the most? This was easy. It was Mourning. Houston had him all

wrong. He wasn't so hard on the edges. As hard as it was for a Knick to say,

Houston actually liked him.

As hard as it was, actually, for a Knick outside of Patrick Ewing to say.

Of course, Ewing is gone to Seattle now. And for Mourning, this is a good

thing. He needed him out of his basketball life, anyway. He needed him out of

New York, out of the East, out of his way to the NBA Finals. Now, the Heat

are the favorites in the Eastern Conference. Now, the Knicks no longer seem

such a legitimate challenge.

|

|

For so long, he was desperate

for the world to see the good man beyond the scowling face, to see the

gentle, generous giant trapped too long within the walls of the bravado. |

|

|

|

For Mourning, this has to be so strange. His whole life has been about

chasing him. As a kid, Mourning was mesmerized over those long arms of Ewing

reaching for the rafters of the Superdome, smacking shots out of a Carolina

blue sky. For the first few minutes of the 1982 national championship game,

Georgetown's Ewing made an art of the blocked shot and inspired a 12-year-old

kid to gather his earnings from a part-time job and purchase a Hoyas T-shirt

after his Chesapeake, Va., school let out the next day.

All over the country, kids cleaned out shelves of those blue-and-gray

models, as close as they could get to living the life of a Hoya Destroya. As

his seventh grade gym teacher, Fred Spellman, remembers, it was unwise to

bring the ball into Mourning in Phys Ed class unless you wanted to bring your

eyeglasses to seventh-period study hall in a clump of shattered pieces.

Within a year, Mourning was 6-4, an eighth grader insisting on

wearing No. 33 for the junior varsity team Spellman coached at Indian River

High School.

"All we did was watch a lot of Georgetown at the time," Spellman said.

"Particularly, we watched Patrick. During that time, Alonzo learned how to

block shots. A lot of big kids, they just swung down and fouled the man. But

Alonzo watched Patrick and learned to tap a shot, to catch it even, anything

but knocking it up in the stands."

Three years later, Mourning was the most treasured recruit in the nation,

"the next Moses Malone," according to one ACC coach. To be sure, this was

flattering, but Mourning didn't want to be Moses. He wanted to be Patrick,

the Georgetown alum who befriended him on campus in the summer before

Mourning started classes there.

"Just working with (Ewing), and him being my idol, gives me so much

inspiration," Mourning said then.

His whole basketball life, Mourning has charted a basketball course using

a compass belonging to Ewing. He was a No. 1 overall pick playing under the

paranoia of Thompson and Pat Riley, spending his summers sweating with Ewing

on the practice floor of Georgetown's McDonough Gymnasium, and his springs

losing to him in the NBA playoffs.

Riley was incredibly uneasy with the parameters of the Mourning-Ewing

relationship. He heard about the summer trips together, the in-season

telephone calls, the dinners on the eve of Knicks-Heat series and wonders if

Ewing hadn't lured Mourning into a web of manipulation.

"If you were to say to Alonzo that Patrick is your big brother and Patrick is

your mentor and Patrick is the guy that watches over you, then the

connotation to that is that somewhere that Patrick can get to

him," Riley warned last season.

"Can that truly be separated in competition?"

This year, it was going to be different. Yes, this was his time. Even so,

Mourning had done the right things over the years and shed the paranoia

inbred to him within that rigid Georgetown culture. Unlike John Thompson and

Ewing, Mourning never seemed so paranoid of everyone. He smiled. He relaxed.

He trusted people. In so many ways, Mourning was past Ewing. This season, he

was supposed to take the final step. He was supposed to go to the NBA Finals.

Ewing was out of his way, and now, Mourning prays it isn't this kidney that's

blocking the path.

Adrian Wojnarowski is a columnist for the Bergen Record and a regular

contributor to ESPN.com. | |

ALSO SEE

Riley chides media for handling of Zo's illness

Lawrence: Dealing with Zo's situation

|